- Home

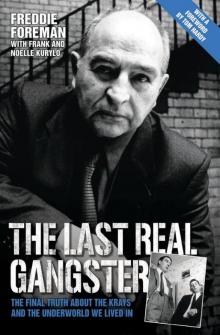

- Freddie Foreman

The Last Real Gangster

The Last Real Gangster Read online

CONTENTS

Title Page

Glossary

Foreword By Tom Hardy

Foreword By Eddie Avoth

Introduction

PART ONE: BROWN BREAD FRED

BY FREDDIE FOREMAN

PART TWO: THE LEGEND OF THE KRAYS

BY FRANK AND NOELLE KURYLO

PART THREE:THE LAST GANGSTER

BY FREDDIE FOREMAN

Copyright

GLOSSARY

At it – engaged in crime

Bird – prison time

Blag – con, cheat or rob

Coat off – deliver a humiliating rebuke

Dabs – fingerprints

Face – professional criminal

Fanny – sweet-talk or deceive

Firm – gang

Firm-handed – as part of, or accompanied by, your gang

Grass – police informer

Long firm – fraud wherein a former paying customer disappears with a large order of goods

Moody – dubious, false

On top – apparent to the police

Plot up – arrive on the scene

Ready eye – robbery under police observation

Shillelagh – Irish ornamental club

SP – starting price, i.e. basic information

SP office – bookmaker’s

Spieler / spiel – unlicensed gambling club

Tickle – proceeds from a robbery

Tom – cockney rhyming slang: tomfoolery = jewellery

Topped – killed

Verbal – uncorroborated written police statement

FOREWORD BY TOM HARDY

So, you are asked to play not one but both of the Kray twins, among the most fearsome London underworld characters of the 1950s and 60s. Many people boasted that they knew the ‘twins’ but none of them had ever met them.

The sole surviving rival gang leader feared by the Krays is the notorious Freddie Foreman. Freddie was regarded as the boss of ‘Indian country’, meaning south of the river. The Krays would only venture across the bridge ‘firm-handed’ because of his fearsome reputation, but they had good reason to be respectful of Freddie and they built their empire upon many of the lessons he taught them.

So, how is it that this underworld enforcer has given so much of his time to coach me in the way the twins walked, talked, scratched their heads and even giggled? Well, Freddie was there and he fiercely believes that, if you’re going to tell the story of gangland London, then you’d better tell it right. Because of his passion, I have had the honour and the pleasure of Freddie’s company over the last few months to capture the essence of the twins, and, if I’ve managed to do so, it’s because I have heard of their mannerisms, their characteristics, first-hand, straight up from a man who knew them before they both became killers.

Tom Hardy

FOREWORD BY EDDIE AVOTH

Freddie Foreman is a gentleman and has always been a good and loyal friend. We have known each other for over fifty years and had some wonderful times together with our families – his children even call me Uncle Eddie

I first met Freddie in the 1960s at The National Sporting Club in London. He used to come see me box at different events over the years. I was the British and Commonwealth Light Heavyweight Champion with a record of 44 wins from 53 professional fights, 20 of those from knockouts.

I retired from boxing in 1972 and went to live in Puerto Banus, Marbella, where myself and a partner opened a high-class restaurant called Silks. Most of our clientele were celebrities and Freddie became a frequent visitor to my restaurant. A few years later, Freddie came to live there, where he became vice-president of the Marbella Boxing Club. He had a licence to put on boxing matches – ‘Spain versus England’ – he invited English boxing clubs such as Eltham South London Boxing Club to take part. I would often go to Freddie’s Eagles Country Club, and sometimes we would go together with our families to Tony Dali’s restaurant, or for a musical evening to Lloyds bar to hear one of the best voices in the business, Lloyd Hulme.

Freddie has been very generous in his support and help (both practical and financial) with my charities such as the Victoria Park Amateur Boxing Club, Ty Hafan and The George Thomas Hospice over the years.

INTRODUCTION

Freddie Foreman has lived his life as an entrepreneur in the criminal underworld. His name has always commanded genuine respect (and sometimes fear) from those who operate outside the law, and even among those who uphold it. Freddie also acquired a fearsome reputation as a troubleshooter for many of the London ‘firms’ – most notably the Kray twins, who relied on him to clean up problems they created for themselves. Infamously, this led to a lengthy prison sentence as accessory after the fact to the murder of ‘Jack the Hat’ (Jack McVitie, 1932–67) – though ‘Brown Bread Fred’ continued to adhere to a strict code of loyalty that the Krays quite often flouted.

While known as the archetypal ‘Godfather of Britain’, Freddie has also spent time in the USA and seven years in Spain. It was from there that he was abducted by the Spanish police and brought back to the UK to stand trial in April 1990 for participation in London’s 1983 £6,000,000 Security Express robbery. Throughout his career, his criminal portfolio has also included major heists such as the bullion raid at Paul Street, Finsbury Square, in the 1960s, and allegations of gangland killings (which Freddie denies).

But, first and foremost, the career of Freddie Foreman represents the intersection of crime and legitimate business. He has owned or co-owned a chain of turf accountants, nightclubs, restaurants, pubs, gyms and residential properties. (At one stage, Freddie was even in partnership with the American Mafia to run gaming rooms in Atlantic City.) He has also lived as a man of principle, protective of his family and loyal to his friends.

We have known Freddie Foreman for many years now, having been instrumental in getting his 1997 autobiography, Respect, written and published.

‘Freddie is a man on his own,’ says Frank. ‘There are two books about him on what he admits he’s done, but you’d have to put ten books out on what he genuinely has done!

‘He’s an old man now, like I am, but when I stop down in London sometimes we go back to his flat for a drop of wine. That’s when he tells you things: Bloody hell, I didn’t know he’d done that! He’ll shut up on you on one or two things he doesn’t want you to know too, but he’s a cracking storyteller, with lovely manners – if you didn’t know him, you’d think he was a bank manager.’

Left-right: Noelle Kurylo, Freddie Foreman, actress Helen Keating and Frank Kurylo.

Frank also operated in a similar respect with the late Ronnie and Reggie Kray, his recollections of whom are supplementary here to the unique Foreman anecdotes. This book follows the format of a photograph album; much of what you see here has never before been published. We hope the accompanying interview text will offer a further insight not only into the life of Brown Bread Fred, but also into the lives of his old associates, the Krays, whose legend stubbornly refuses to die.

Frank and Noelle Kurylo

PART ONE

BROWN BREAD FRED BY FREDDIE FOREMAN

I was born on 5 March 1932. This first picture was taken when I was two. I had rickets and they put me in the nursery to build up the strength in my legs. I was definitely undernourished because we were really poor, down in Sheepcote Lane, Battersea. Just the old gas mantles, no electricity, no real fire, only a stove to cook on, no heating. We’d got a radio with an accumulator, a battery filled with the acid you had to go out and buy. There was a toilet outside, naturally, and an old mangle for the washing – which I used to swing on with my mother. ‘You’re a strong little boy, Freddie!’ she used to say, geeing me up.

We

had a garden out the back. I was the youngest of five brothers – that’s my brother Wally on his bike on the next page. We had a pigeon loft at the back and they used to go down to Battersea Bridge and nick the pigeons out of the bridge, which was a dangerous thing to do. My brothers Herbie and Wally used to go swimming down there, jumping in the Thames. Our father warned them not to do it, but as he came by there one day he recognised their shoes, so he nicked them and brought them home with him. Of course, they came home barefooted and got into trouble!

They were real hard times, real poverty. Then we got moved because just across the road was a railway with stables in front of it and the other end was a Gypsy camp with caravans. It was one of those areas with vendors coming down – you had the muffin man, salt sellers and knife sharpeners. Then there was Prince Monolulu: ‘I’ve got a horse!’ The first black man we ever saw, he was an infamous tout. As kids we would follow him down the street; he’d have robes and a turban on. All the women used to run out and he’d give them a bit of paper with a bet on it. They all liked to gamble if they could afford sixpence, but he’d give the name of every horse in the race, so one of them would go, ‘I’ve won, I’ve won!’ One of the horses had to come in, that was his graft.

It was all tallymen then, having it on the never-never: sixpences and pennies to clothe the kids. In 1939 they moved us to Croxteth House on the Wandsworth Road. There was a row of houses and behind that was a big factory. We were the first people to move into this brand-new block of council flats at Union Road, Clapham, and we were delighted because we had an indoor toilet with an actual bathroom instead of the old tin bath that used to come out every Friday night – and I was the last one in, with all the scummy old water, being the youngest. But now we had a nice kitchen, electric plugs and a little fireplace. There were three bedrooms, too, whereas when we lived in Sheepcote there were four of us to the bed, top and bottom, and my eldest brother Herbie over in a little bed in the corner.

No sooner were we there than war was declared. The below picture was taken at the beginning of the Second World War. That’s my father, Albert, and my mother, Louise, with me (centre) and my brother Bert (right) in Brighton.

My brothers had good jobs at the time, working in Whitehall Court as liftboys, wearing little uniforms. The people who lived there would treat us to a hamper at Christmas, and to get a £5 note was amazing! We were just getting on our feet as the boys were bringing some money back into the home.

My father had been at the Somme. He served in the King’s Royal Rifles during the First World War. A trainee blacksmith who was shoeing horses, he was conscripted at sixteen or seventeen. He got wounded in France: his arm was shattered and all the muscles were gone. As he wasn’t strong enough to hold a horse and put a shoe on it, he lost his trade. He just walked around London, never had a bike, and learned ‘the Knowledge’. So that’s what he went into: the old taxi with the hooter on the side, in the open air, with a bit of tarpaulin in the back. That was a luxury, but the cab driver wasn’t supposed to be comfortable! Out in all weathers, open to the elements. He used to bring the cab round to the flats and the kids loved the hooter. They would run and jump on the running board.

So, the Second World War started and then the air raids began. I remember the first air raid on Wandsworth Road – everyone was looking at the trails in the sky on a sunny Saturday afternoon. There was a dogfight going on up there, and it was quite an experience to see it. Then of course people realised what was going on: it had been a ‘phoney war’ as they later called it, up until the first raids came.

With my nearest brother, Bert (who was too young to be conscripted), I was evacuated to Woking. We were sitting in a hall; Bert was picked by a family and toddled off, and I was the last one left. I don’t know what was wrong with me!

I finished up with a family, but it was dirty and rotten, and I had to sleep in a bed with other kids. The old man came in from the pub and never acknowledged any of the family, just went up to bed. One of the kids I slept with had TB – he used to cough up blood. It was horrible. I remember the woman standing me up in the sink to wash me, and I didn’t like that. I was really unhappy there. After I’d had it good with my brothers all round me, Herbie, Wally and George had gone off to war. I was the youngest, and then there was Bert (above centre, on page 9 – after he’d joined the Navy), George (left), Wally (right) and Herbie (centre, bottom). Bert passed away during the interviews for this book, on 25 November 2014.

After that I was billeted to Brighton, with a nice, kind woman. That’s my parents visiting Bert and me there, with my dad’s sister, Auntie Emma (sitting), who’d lost a leg due to illness. I thought it was great in Brighton.

Then we went home and the Blitz really got started. All of a sudden I was in the thick of it. The factory on the other side of the road turned into a munitions manufacturer. We were sitting on a big target! They aimed for that every night – they hit it twice. Every street in the area was devastated. They used to train troops there because it was like a battlefield: all the conscripts with cap guns hanging on the end of their rifles, smoke bombs as hand grenades, even live ammunition. We were made to keep away, but we watched all the soldiers in the streets. It was like a game to us; it wasn’t the real thing.

Across the road from us they put a barrage balloon and an ack-ack gun, and there were WAAFs (members of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force). You could sit at your window watching it, and on this one particular night my father said, ‘I’m not going down that shelter.’ They’d built one at the back of the house, you went down underground and there was an escape hatch at the end of it. You’d get forty, fifty people down there in iron bunk beds. It was all right for kids to play and run around there, which I used to do, but as a family we wouldn’t go down because there was just a corner with a bucket in it and a little sheet. It stank of carbolic.

All night long there were noises: couples making love and everything else. It was enlightening, I suppose; educational. But my old man wouldn’t stand for it. We used to stay in the corner of the flat. In that one section my mother got all the pillows, covers and eiderdown, and put them all on top of us. That went on for ages.

But the Blitz got really heavy; it was coming down bang-bang; they were trying to iron that factory out. We were in bed one night at the weekend and it’d just started. My brother Bert said, ‘Come on, we’ll have to get out.’ I was still in bed, but all of a sudden there was an explosion! I was lifted out of bed and onto the floor. All the windows came in. Bert was saying, ‘Come on, Fred, get your things on!’ I was standing up on the bed and he was trying to dress me; I was only little. It was the first time we went down the shelter but we stayed from then on; it shook us up a lot. It went dark then. There was a pub across the road where my father used to play darts; he came home one night and it got a direct hit. They were all fucking killed, all of them local neighbours; he’d come home just in time.

I finished up being evacuated to Northampton, but Bert was old enough to join the Navy. Then there was a lull in the bombing and they thought, ‘That’s all right, he can come home now.’ But there wasn’t a family now: all the boys were in the forces; there was only my mother and father and me.

Bert was out in the Channel when they were attacking the torpedo boats that were sinking the Atlantic convoys; his ship got a torpedo in the bow. His captain said to batten down the hatches but there were still people down below. Dead ruthless, but they had to sacrifice them to save the ship. They got back to Portsmouth in reverse – they couldn’t go forward with a hole in the bow.

Bert sailed around Australia and the Pacific. He saw a bit of action, though not as much as George, Herbie (whose wartime military record you can see to the right, which we’re very proud of) and Wally. He was on the D-Day invasion, but George was on a ship sunk out in the Atlantic and the other two were in Paris. George’s ship, the Fitzroy, went down in four minutes. We heard it broadcast on the radio by Lord Haw-Haw (the wartime traitor William Joyce): ‘The Germ

an Imperial Navy today sank the minesweeper HMS Fitzroy. All hands were lost.’ It was propaganda but there was an element of truth in some of it.

George was a stoker and he’d just come out of the stokehole in his boiler suit. He was making a cup of tea at the end of his watch. When the torpedo hit it capsized the ship. The ladder to the escape hatch was across the ceiling, so he had to clamber hand over fist to get out. ‘Abandon ship! Abandon ship!’ He didn’t need telling twice, he just dived straight over the side. George was hanging on to a Carley float (a life raft supplied to warships) instead of a lifeboat. Another minesweeper picked them up, but he was out there in the Atlantic for quite a few hours. There were only a few survivors.

But we’d heard that all hands were lost, so we thought he was dead. I was looking over the balcony a few days later. My mother and father had shed plenty of tears, but all of a sudden someone walked over in a boiler suit, plimsolls and a raincoat. He waved his sailor’s hat. I could hear my mother in the kitchen, washing the pots and pans.

‘Muvver, quick, come out ’ere! It’s our George!’

‘George … our George?’ She was drying her hands on her wraparound pinny as he came across the flats. We ran down the end of the balcony and there were tears. The old man went down the Portland Arms in the Wandsworth Road that night and they all had a piss-up. One minute we thought he was dead, the next he was alive. That’s why I’ve always stayed close with George.

The Last Real Gangster

The Last Real Gangster